Does a subgroup of minimally-speaking autistic individuals have close-to-normal comprehension skills? A critique of Belmonte et al., 2013

One of the pro-FC individuals platformed at last January’s NIH-sponsored webinar on Minimally Verbal/Non-Speaking Individuals With Autism was Matthew Belmonte, a visiting researcher at the Com DEALL Trust, Bangalore and the brother of someone who, Belmonte claims, communicates valid messages through the Rapid Prompting Method. During his turn in a session entitled “a panel of stakeholder perspectives”, starting at around 17:00, Belmonte notes that, while facilitated communication (FC), Rapid Prompting Method (RPM), and “similar methods” do, as he puts it, “admit influence,” many people are investing time in them. The important questions regarding any one of these methods, he concludes, are “Could it work?”, “If it works, how might it work?”, and “If it works for whom might it work?”. He continues:

…we have found in our own work that about a third of minimally verbal, uh, minimally speaking people with autism in our clinical sample have a severe oral motor impairment and receptive language much, much greater than expressive language. We believe that it is this subsample that might be the candidates for something like this.

Matthew Belmont and others at the NIH-sponsored webinar: Minimally Verbal/Non-Speaking Individuals with Autism: Research Directions for Interventions to Promote Language and Communication (Day 1) (NIH, 2023)

The work he references is Belmonte et al. (2013), a paper entitled “Oral motor deficits in speech-impaired children with autism.” This paper is among just a few “participant-suggested” readings listed on the webinar website—along with Jaswal et al.’s infamous eye-tracking study (critiqued here), which purports to find evidence for a variant of RPM known as S2C, and two works attributed to Grant Blasko, a non-speaking individual who has been subjected to both FC and RPM.

So let’s take a closer look at Belmonte et al. (2013), an article we have not yet critiqued on this website. Belmonte et al. report one main finding: namely, that about a third of the autistic children in their early intervention clinic (out of a total of 31) had oral motor difficulties that were associated with expressive language problems (i.e., problems with speaking) that were worse than average compared to receptive language problems (i.e., problems with comprehension).

This finding, in part, is totally unsurprising. Oral motor problems affect your ability to speak but not your ability to comprehend. More notable is that a third of the autistic children in the clinic had oral motor difficulties—a frequency much higher than is generally reported (see Kim, 2014). But perhaps the most surprising claim appears at the end of the article’s abstract, where Belmonte et al. propose that the motor difficulties in autism extend beyond problems with oral-motor control to include “more basic skills such as pointing.”

It is these last two claims that potentially lend support to FC—in particular, to the FC-friendly notion that autism is primarily a motor disorder; that minimal speech in autism results primarily from oral-motor problems (often called “apraxia of speech”); and that autistic individuals also have difficulty making pointing gestures, such that, when pointing to letters on keyboards, they need the kind of assistance (physical support; prompting) provided by FC, RPM, and S2C facilitators.

So to what degree do these claims hold up?

As far as pointing goes, besides saying that pointing is one of the skills taught at their clinic, Belmonte et al. provide no evidence that any of their clients actually struggle to point. One of the measurement tools used in their study, the Com DEALL Developmental Checklist (CDDC), does include assessments of fine motor skills, but neither Belmonte et al. nor the one reference they cite on this tool, Karanth et al. (2010), tell us which fine motor skills are measured or whether they include pointing. The only other mention of pointing occurs at the end of the paper:

There remains of course the potential that fine motor impairments could impede use of alternative and augmentative communication devices, because open-loop motor control which is unintegrated with sensory feedback (Haswell et al., 2009) leads to errors in pointing with a finger or hand to select amongst multiple response options.

The paper Belmonte et al. cite here, Haswell et al., (2009), makes no mention of pointing. Haswell et al.’s experiment had children hold a robotic arm in one of their hands and reach with it to capture toy animals. The researchers examined how well the children controlled the robot when it “perturbed the children's arm movements by producing a force field.” Comparing the performance of their autistic and non-autistic subjects, Haswell et al. found that there were differences in performance, but also that “in the baseline period in which no perturbations were present, both ASD and typically developing groups produced straight reaching movements.” Since pointing typically involves straight reaching, and typically occurs without perturbations from force fields, Haswell’s results suggest that, consistent with our other posts on this subject, pointing difficulties are not a common characteristic of autism spectrum disorders.

What about significant oral-motor problems or apraxia of speech? There is some support for oral-motor difficulties affecting expressive language in minimally speaking individuals with autism. Chenausky et al. (2019), for example, report symptoms of “likely” apraxia of speech in about a quarter of 54 minimal speakers whose videos they analyzed. But oral-motor problems are not generally reported as the main obstacle to communication in autism (see Kim et al., 2014).

Furthermore, though you wouldn’t know it from the NIDCD webpage, several more solid papers (larger sample sizes; measurement tools more clearly described) have been published since Belmonte et al. (2013) that reach rather different conclusions. One is Yoder et al. (2015). Examining a sample of 87 autistic preschoolers, all of whom were initially nonverbal, Yoder et al. find that motor skills, including oral-motor skills, were not significant predictors of expressive language. Rather:

responding to joint attention, intentional communication, and parent linguistic responses were value-added predictors of both expressive and receptive spoken language growth

In other words, language skills—both receptive and expressive—correlate not with motor skills, but with what most people consider to be core autism symptomology.

Another example is Mody et al. (2017). Examining 1781 participants ranging from 2 to 17 years of age, Mody et al. find “significant positive associations” between fine motor skills and both expressive and receptive language skills. In other words, poor motor skills are associated not just with speech problems, but also with comprehension problems. Indeed, Mody et al. found that the motor difficulties that were correlated with comprehension included not just fine motor skills, but also gross motor. In addition, they find an association between both gross and fine motor skills and social interactions, speculating “that the demands of an impaired gross motor system may leave the child on the autism spectrum with fewer resources for developing joint attention abilities.” Their research thus suggests that motor skills, in their contribution to communication problems, cannot be disentangled from the core social symptoms of autism, which in turn impede both speech and comprehension.

Another article, McDaniel et al. (2018) focuses in particular on receptive vs. expressive vocabulary (word comprehension vs. word use). Among its findings are three that are both at odds with Belmonte’s implications and problematic for FC:

Compared to typical children, the 65 autistic participants exhibited smaller receptive–expressive vocabulary size discrepancies. That is, “The children with ASD tended to exhibit comprehension of fewer words than expected relative to the number of words they said.”

Participants’ oral-motor skills were not significant predictors of the co-occurrence of spoken vocabulary deficits with relatively large receptive vocabularies.

What leads to a receptive vocabulary that is, as is the case with typical children, large relative to expressive vocabulary is a factor that taps into the core social deficits of autism: what McDaniel et al. call “attention toward a speaker.”

Indeed, based on these findings, McDaniel et al. suggest that speech in autism is impaired not because of oral-motor difficulties or apraxia of speech (contrary to Chenausky et al.’s impressions from the videos they rated) but, rather, from a failure to tune in and tune up to speech (see also Shriberg, 2011)—a possibility we discussed in an earlier post.

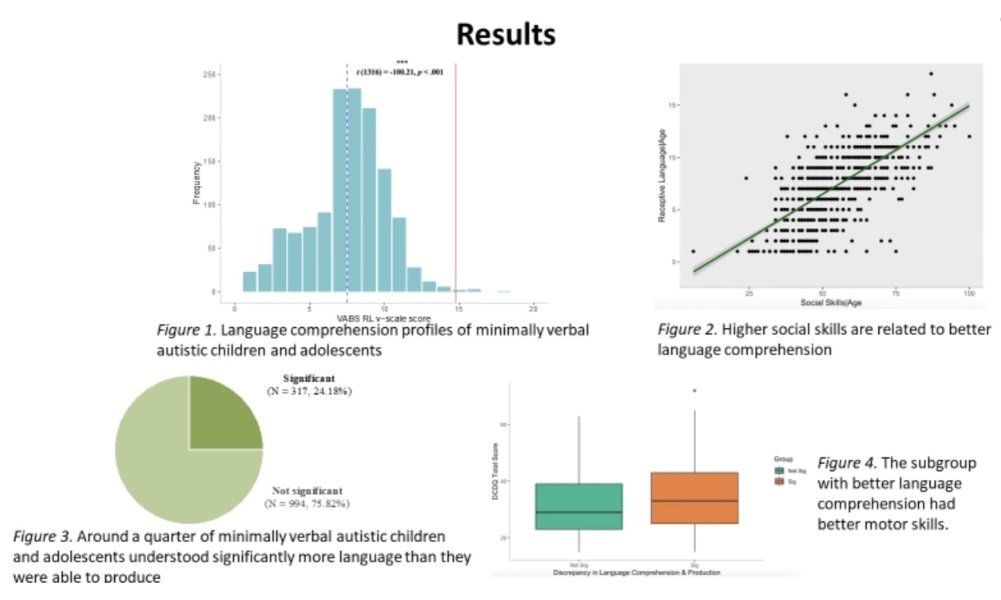

Finally, Chen et al. (2023), summarized in this video from the recent INSAR conference (and also discussed in this recent blog post of ours), reported one more finding that is problematic both for FC and for Belmonte. While there exists a subset of minimal speakers (about 25%) in which receptive skills are relatively high relative to expressive skills, the receptive skills even of this unusual subgroup:

are still lower than those of non-autistic individuals

are positively associated with motor skills.

Screenshot from Chen’s INSAR video

That is, as Chen puts it in her video:

[I]n this subgroup, motor skills emerge as the only significant factor predicting the discrepancies between receptive and expressive language above and beyond all other factors. And those with better motor skills are more likely to have much better receptive language than expressive language.

Oddly, some of these later findings are consistent with two findings that Belmonte et al. report in their otherwise much-outdated paper: namely, that receptive language correlated with gross and fine motor skills, and that both receptive and expressive language correlated with fine and oral motor skills.

So while Belmonte might still think, 10 years on, that his 2013 findings support the notion that there’s a group “that might be the candidates for” FC, RPM, and/or S2C, his own empirical findings appear to be less biased than the conclusions he draws from them.

REFERENCES

Belmonte, M. K., Saxena-Chandhok, T., Cherian, R., Muneer, R., George, L., & Karanth, P. (2013). Oral motor deficits in speech-impaired children with autism. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience, 7, 47. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2013.00047

Chen, Y., Siles, B., Liberti, G., Tager-Flusberg, H. (2023). Discrepancies in Receptive and Expressive Language Profiles in Minimally Verbal Autistic Children. INSAR, 2023.

Chenausky, K., Brignell, A., Morgan, A., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (2019). Motor speech impairment predicts expressive language in minimally verbal, but not low verbal, individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism & developmental language impairments, 4, 10.1177/2396941519856333. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941519856333

Haswell, C. C., Izawa, J., Dowell, L. R., Mostofsky, S. H., & Shadmehr, R. (2009). Representation of internal models of action in the autistic brain. Nature neuroscience, 12(8), 970–972. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2356

Karanth, P., Shaista, S., & Srikanth, N. (2010). Efficacy of communication DEALL--an indigenous early intervention program for children with autism spectrum disorders. Indian journal of pediatrics, 77(9), 957–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-010-0144-8

Kim, S. H., Paul, R., Tager-Flusberg, H., & Lord, C. (2014). Language and communication in autism. In F. Volkmar, R. Paul, S. J. Rogers, & K. A. Pelphrey (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (4th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 232–363). Wiley.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118911389.hautc10McDaniel, J., Yoder, P., Woynaroski, T., & Watson, L. R. (2018). Predicting Receptive-Expressive Vocabulary Discrepancies in Preschool Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR, 61(6), 1426–1439. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-17-0101

Mody, M., Shui, A. M., Nowinski, L. A., Golas, S. B., Ferrone, C., O'Rourke, J. A., & McDougle, C. J. (2017). Communication Deficits and the Motor System: Exploring Patterns of Associations in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 47(1), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2934-y

Shriberg, L. D., Paul, R., Black, L. M., & van Santen, J. P. (2011). The hypothesis of apraxia of speech in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(4), 405–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1117-5 [4] Aside from words that label pictures, most written words cannot be learned in

Yoder, P., Watson, L. R., & Lambert, W. (2015). Value-added predictors of expressive and receptive language growth in initially nonverbal preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 45(5), 1254–1270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2286-4