ASHA 2025: The Empty Review of FC/RPM/S2C/Spellers Method and its aftermath

My news roundup of two weeks ago captured only a subset of the FC/RPM/S2C/Spellers Method developments that were unfolding the whole time I was posting about holoboards and hololenses and letterboxes. Today I’ll turn to this past November’s ASHA conference, where I was a co-presenter, along with Ralf Schlosser, Bronwyn Hemsley, Howard Shane, and Russ Lang, of a talk entitled “Minding Myths: Systematic Review of Rapid Prompting/Spellers Method and Critical Appraisal of the ‘Telepathy Tapes’”

The talk (our slides are here) described the results of our latest systematic review of RPM/S2C/Spellers Method. We also discussed additional evidence against these methodologies (RPM/S2C-generated message content conflicting with findings on comprehension skills in non-speaking autism; RPM/S2C-generated messages that purportedly show telepathy actually showing facilitator control), along with the associated harms (professional, financial, educational, sexual, custodial, and misinformational).

We felt the talk was well-attended and well-received, but as soon as the Q & A began, a detractor shot out of her seat and over to the mic. “Telepathy aside,” she said, what about people who use these methods and become independent typers, like Jordyn Zimmerman and Danny Whitty?

I ended up answering her first, and I said something like this:

Jordyn Zimmerman was never subjected to any form of facilitated communication. If you look her up on YouTube, you’ll find a video of her presenting at a Board of Education meeting that includes the message “I can speak. I can even have a conversation with you.” As for Danny Whitty, I’ve never seen a video of him independently typing a spontaneous response to an unrehearsed question.

Danny Whitty, while described as “non-speaking,” stands out from most FC/RPM/S2Ced individuals in one way: he has the decoding skills to sound out letter sequences after he selects them. This might look to some like a form of communicative independence, but it’s actually a manifestation of hyperlexia. Hyperlexia is relatively common in autism but does not entail comprehension. Two other FCed individuals, Naoki Higashida and Jamie Burke, also have the ability to pronounce what they type out after it’s typed out.

Our detractor was not happy with my answer, or with our talk, and posted a, shall we say, emotional (I’ll avoid the word “histrionic”) reaction on Instagram that evening. The next day, at the start of a Q & A on Gestalt Language Processing (another non-evidence-based practice) that Bronwyn and I attended, our detractor suddenly appeared and went straight to the mic—this time to praise the talk, but also to vent about a really upsetting talk she’d heard the night before. Not realizing that we were sitting behind her, or that there were others present who had also heard our talk, she proceeded to misquote us. Before we could object, several others in the audience shouted “That’s not what they said.”

(The world would be a better place if more people realized that when they blatantly warp other people’s words they undermine their own credibility.)

We had a long conversation with her afterwards in which, among other things, she expounded upon “whole body apraxia” in nonspeaking autism (that longstanding FC-friendly re-analysis of autism as a motor disorder that harks back to Douglas Biklen) and claimed that the work of Stewart Mostofsky supports this notion (as we discuss here, it does not). We parted on nominally friendly terms, but somehow I doubt she’s stopped trashing us.

A week later, in a Thanksgiving Surprise, we became aware of some additional detractors—a baker’s dozen of them, in fact. Calmer and more measured than our in-person detractor (we’re not sure they attended the conference, or our talk, but they managed to access our slides) they wrote an open letter to ASHA introducing themselves and their research program... and objecting to our content.

Calling themselves “a collective of scientists and practitioners who are working to understand apparent savantism and authorship in nonspeaking autistic people,” all, or nearly all, of the thirteen signatories are people who have outed themselves elsewhere as believing in (and in some cases being professionally committed to) paranormal phenomena.

Just sayin’.

Assuring ASHA that they’re performing their research “in a scientifically rigorous and open-minded way, so we can truly characterize the capacities of these individuals [non-speaking autistics]” they state that they are in the process of “conduct[ing] rigorous trials examining authorship.” They add that their preliminary results are so “compelling and informative” that they “hope to present our authorship investigations at ASHA 2026.”

I must say, I’m looking forward to that.

For now, though, their goal is “to communicate some facts about the state of the field, and some concerns about ASHA’s position with respect to spelling methods.” In particular, they wish to discuss what they call some “scientific mis-steps made in a recent seminar in your 2025 conference program.” specifically our presentation.

Here, in order of appearance, are some of the things they say, followed by my responses:

The Collective: [W]e are including nonspeaking and minimally speaking people... as informed participants and co-researchers as we conduct rigorous trials examining authorship.

KB: It would be problematic to accept a paper based on any research with non-speaking participants whose consent is obtained through S2C-generated output.

The Collective: Apraxia, which disrupts the planning and execution of purposeful movement, often prevents nonspeaking individuals from showing how much they truly comprehend because all intelligence testing is motor based.

KB: The motor requirement of the language comprehension tests is the ability to point to pictures. There is no evidence of a motor impairment that prevents autistic individuals from pointing to pictures, and the only article you cite, Tierney et al. (2015), is only about apraxia of speech.

The Collective: In our interactions with schools, parents, and communities, we are concerned that minimally speaking individuals are being underestimated.

KB: “Interactions” and “concerns” aren’t data, and the article you link here (Courchesne et al., 2015) does not find that the language skills of autistic individuals have been underestimated; only their nonverbal skills have been underestimated, and only by certain tests in the case of some individuals.

The Collective: [T]heir literature review excludes all papers that could meaningfully address the question of authorship.

KB: What our systematic review excluded were papers in which authorship was not studied, or in which the researchers merely inferred that a person had authored a message based on their behaviors or the stylistics of their messages—neither of which is enough to establish authorship. [See our section on misleading articles.]

The Collective: The authors ignore, for instance, an eye-tracking study in Nature [sic—they link to the wrong study; the actual one is here] from the University of Virginia because it had been “criticized” by one of the presenters.

KB: The paper wasn’t ignored; it was deemed not to have addressed authorship. Its research question centered on whether minimally speaking autistic individuals look ahead at things (letters) before pointing to them—a common behavior that the authors assume indicates not just intentional pointing, but also intentional communication, and also that this somehow rules out facilitator influence (see Beals, 2021 and Vyse, 2020 for critiques of these and other leaps of logic in this infamous eye tracking study, whose first author has a daughter who uses S2C and therefore a major [undeclared] conflict of interest).

The Collective: [T]here is an attempt here to harness stigma around the phenomenon of telepathy and other nonlocal capacities as a way to discredit communication via letterboard or keyboard.

KB: Telepathy, as we pointed out in our presentation, does not explain documented message passing failures in which the facilitator was merely blinded (and not shown a different stimulus).

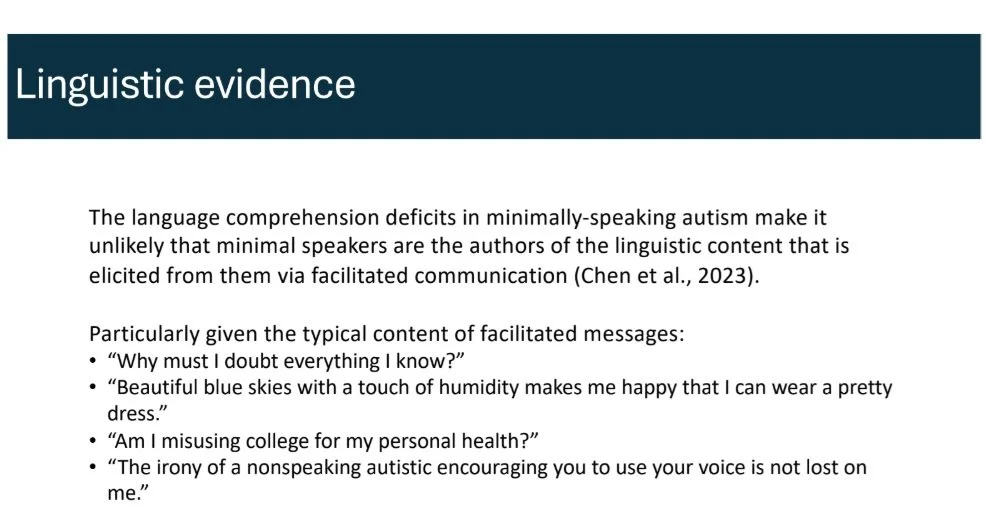

The Collective: The authors also determined that no qualitative observations of language or stylistics would be used in their analysis, so they rejected any tests of authorship employing these methods. Yet in their slides they reference the same types of methods to prove other points (e.g., the Linguistic Evidence slide).

KB: The slide you’re referring to here is my slide showing examples of the sophisticated language generated through FC/RPM/S2C, which conflicts with the low levels of language comprehension found in studies of minimally-speaking individuals. One cannot be the author of a message that is composed of words and phrases one does not understand.

The Collective: Finally, when it came to providing evidence for their assertion that spelling methods cause harm, the authors highlighted malpractice in their presentation, making it appear that the majority of practitioners trained in spelling methods are causing harm. Meanwhile, malpractice and abuse occur in every field (including within ASHA-supported environments)...

KB: It was the extreme nature of the harms (professional, financial, educational, sexual, custodial, and misinformational), not the number or percentage of harms, that our slides described. Fortunately, harms of this nature are not found in every field.

The Collective: ...and it is reasonable to assume such abuse is much less likely with training methods like RPM and S2C that are geared towards autonomy and developing independence.

KB: There is no evidence that RPM and S2C have ever led to autonomy and independence, while there is plenty of evidence that evidence-based methods have.

I suspect we’ll be hearing more from this group soon—but will what we hear include the results of their “rigorous trials examining authorship”?

REFERENCES

Beals, K. (2021). A recent eye-tracking study fails to reveal agency in assisted autistic communication. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 15(1), 46–51.

Courchesne, V., Meilleur, A. A., Poulin-Lord, M. P., Dawson, M., & Soulières, I. (2015). Autistic children at risk of being underestimated: school-based pilot study of a strength-informed assessment. Molecular autism, 6, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-015-0006-3

Jaswal, V. K., Wayne, A., & Golino, H. (2020). Eye-tracking reveals agency in assisted autistic communication. Scientific reports, 10(1), 7882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64553-9

Tierney, C., Mayes, S., Lohs, S. R., Black, A., Gisin, E., & Veglia, M. (2015). How Valid Is the Checklist for Autism Spectrum Disorder When a Child Has Apraxia of Speech?. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP, 36(8), 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000189

Vyse, Stuart. (2020, May 20). Of Eye Movements and Autism: The Latest Chapter in A Continuing Controversy. Skeptical Inquirer.